Vincent Canby’s review of, “The Passenger”

Canby’s “Film View,” review was published April 20th, 1975, and was titled, “Antonioni’s Haunting Vision”.

As if he were a member of some privileged order, Michelangelo Antonioni is allowed to see things the rest of us cannot. In his stunning new film, “The Passenger,” he shares that privilege with us. His camera's eye is a laser that transforms everything it sees into a more precise definition of the thing represented—objects, people, movements, landscapes. Yet the definition of the thing represented—and this is the rub—becomes increasingly ambiguous the closer Antonioni's camera gets. The same thing happens when you say the same word over and over again so often that finally only the sound is left. We return to essentials.

This is one of the haunting effects of “The Passenger,” a suspense melodrama, a story so basically conventional that it isn't until you're at least half‐way through it you realize it's a magnificent nightmare, and that you are on the inside looking out. More effectively than any other film he has made, “The Passenger” translates Antonioni's concern with the quality of contemporary life into non‐esoteric film terms. Even more successfully than in “L'Avventura” and “Blow‐Up” he achieves a balance between psychological substructure and intellectual superstructure, the weight of which capsized “Zabriskie Point,” his last film, even before it had left the dock.

“Zabriskie Point” was a collection of handsomely illustrated, neo‐radical ideas, a meditation on America not of the first interest, for which a love story of sorts had been concocted, but it was a narrative that had no life of its own.

“The Passenger” is a fascinating tale of flight and pursuit that moves non‐stop across the screen. Its intellect is more apparent in the way it looks (the best movies are what they look like) than in anything that anybody says. It's there in the beautiful opening sequence, which I will try to describe, and in the extraordinary closing sequence, which I won't, not only because it would be giving the story away but because it's the sort of cnematic tour de force that must be discovered for oneself.

This ending has some of the breathtaking quality of the ending of Bunuel's “Tristana,” though the two sequences have nothing specifically in common. Neither sequence is particularly fancy, but each in its way rediscovers a narrative device unique to films.

The opening sequence of “The Passenger” is pictorial ??xposition of special order: a man (Jack Nicholson) Is searching for someone or something through North Africa, ?? the outskirts of cities, in rural villages. He is scarcely acknowledged. People look through him, or away. In a cafe stwo black men help themselves to his cigarettes and turn back to their own affairs. Later a small Arab boy materializes and leads him and his Land Rover into the desert. There The boy motions the man to stop. The boy gets out of the car and disappears. The man can see nothing but desert and some distant mountains. No place for the boy to escape to. The dry heat and the seeming clarity of the desert light at high noon make him a little giddy.

Then, In the distance, there appears an Arab atop a camel riding leisurely across the sands. The man waves to the Arab and calls. The Arab and his camel pass close by. The Arab nods to the man, but distantly, as if he were on ship whose course was being directed by others. The Arab goes on his way at the same unbroken pace. The man climbs back into the Land Rover, turns on the engine and quickly allows himself to get stuck in the sand. He gets out once more and kicks the half‐buried tire. It is the last straw. It's also his own bloody fault. At last he's reached the end of the line.

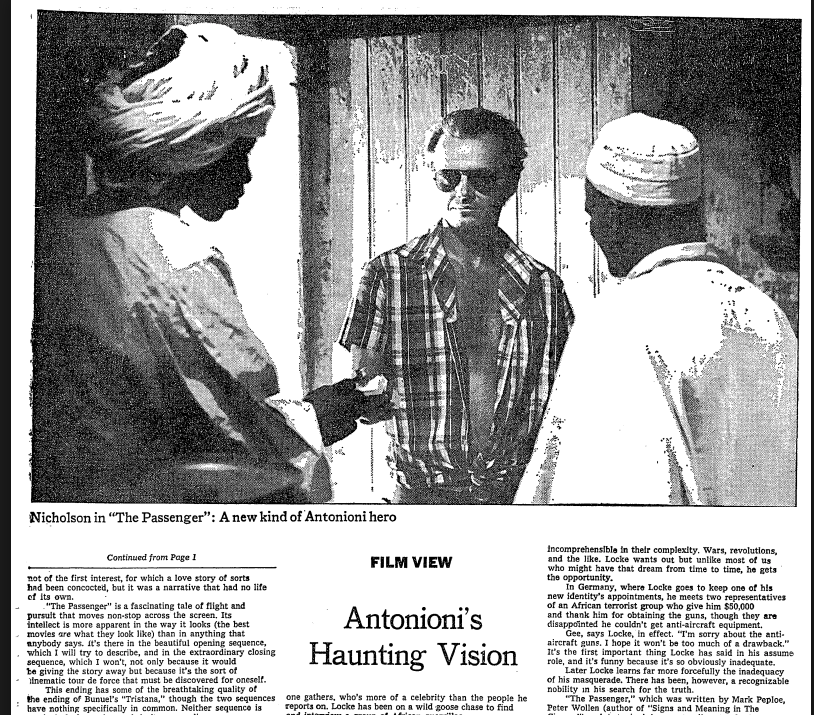

The man Is a television news personality named Locke, English‐born, American‐bred, the sort of reporter, one gathers, who's more of a celebrity than the people reports on. Locke has been on a wild goose chase to find and interview a group of African guerrillas.

Locke returns to his fleabag hotel in the desert on foot. You suspect that he might be a Maugham character doomed to an exotic end in civilization's outpost. Not so. When a passing stranger, an Englishman about Locke': age, weight and height, dies suddenly of a heart attack at the hotel, Locke makes a choice. He assumes the man's identity. Locke picks up the man's name, passport, wardrobe and appointments book, and then sets out to discover who he now is.

Thus begins “The Passenger,” which follows Locke on his search from North Africa to England to Germany to Spain. In the course of his travels he meets a pretty, calm, unflappable girl (Maria Schneider), who is known only as The Girl. The Girl is an architecture student but she exists only to help and comfort Locke. As much as he has known what the end of his search must be, he has known about the girl even before he meets her in Barcelona. Earlier, in London, he had seen her sitting on a park bench and they had recognized each other.

Antonioni doesn't spend too much time convincing us of the desperation of Locke's life that would make him so easily assume another's identity. He has been unhappily married, we are told, though the wife (Jenny Runacre) is hardly a harridan. We are also told he is fed up with his career, freezing on film those moments of history that never truly tell the entire story. He has been in the business of reducing to comprehensible terms—to television merchandise—events that may be incomprehensible in their complexity. Wars, revolutions, and the like. Locke wants out but unlike most of us who might have that dream from time to time, he gets the opportunity.

In Germany, where Locke goes to keep one of his new identity's appointments, he meets two representatives of an African terrorist group who give him $50,000 and thank him for obtaining the guns, though they are disappointed he couldn't get anti‐aircraft equipment.

Gee, says Locke, in effect. “I'm sorry about the antiaircraft guns. I hope it won't be too much of a drawback.” It's the first important thing Locke has said in his assume role, and it's funny because it's so obviously inadequate.

Later Locke learns far more forcefully the inadequacy of his masquerade. There has been, however, a recognizable nobility in his search for the truth.

“The Passenger,” which was written by Mark Peploe, Peter Wollen (author of “Signs and Meaning in The Cinema”) and Antonioni, is open to all sorts of solemn interpretations, a lot of them involving the use of the word “alienation,” which may be the most boring word to gain wide currency in criticism in the last 20 years.

Once you leave the film's narrative level to ponder its other meanings, you are on your own. “The Passenger” shouldn't be scrutinized and deciphered like a top‐secret NATO message. It's a poetic vision. Its images, as perfectly illuminated as a night landscape by a flash of lightning, suggest all sorts of associations, from “The Odyssey” to other movies, including pot‐boiling, multinational coproductions about Interpol agents.

Locke, a role that Jack Nicholson assumes with such grace and ease that one almost forgets he's an actor, comes out of the barren world of earlier Antonioni films, but unlike earlier Antonioni characters he makes a decisive choice that sets him apart from his predecessors, who were too busy just trying to cope to make decisions of such magnitude. In his way Locke is a much more committed, much more revolutionary character than the pea‐brained radical in “Zabriskie Point.” He's also a much more appealing character than the photographer “Blow‐Up,” a man who remained always outside his pictures.

“The Passenger” marks Antonioni's triumphant passage from the concerns of the nineteen‐fifties and nineteensixties, when we seemed to be standing still, to those of the nineteen‐seventies, when events have given us the guts to choose, perhaps to move on.